Rightist Factional Alliances in the Spanish Civil War

Parallel Institutions and Unification Under Rightful Authority

The Spanish Civil War continues to attract increasing attention in our sphere for what I believe to be the following reasons:

It’s the conflict that rhymes the closest with what we are likely to face here in the United States1

The good guys beat the communists

We have heard the Myth of the 20th Century’s death rattle, so the lesser known battles of the interwar period are back on the table for study

That Myth crumbles almost immediately when the situation in Spain is examined by faithful Christians, as the battle lines cannot be made clearer: a broad coalition of Christian Crusaders defended their faith, their culture and families against murderous Communism. When reading the English language material produced by libtard academics, the lies jump off the page, and the true beliefs of Spain’s Republican communists, socialists and anarchists, who never intended good faith negotiation or cooperation with the traditionalists, are loud and clear. Their republic was a vehicle for revolution identical to those seen in Russia and France, a great bloodletting by a generation of destroyers. We know that the libtards desire the same thing here, so when they excuse away the mass murder, torture, rape and starvation of Spaniards, they are excusing away their intent to do the same to us and to our children.

If we conclude that all of the above points are true, we must then ask ourselves what lessons we can learn from the Spanish experience to improve our own positions. How and why did the good guys beat the communists? One could simply say, “God was on their side,” but God was certainly not on the side of the Bolsheviks or the anti-Christian agitators in France. No – God’s people simply failed to recognize the times they were living in before it was too late. The Spanish had the benefit of foresight, thanks to the French experience just over their border and the more recent Russian catastrophe on the opposite side of the continent. What did the Spanish right do correctly in order to win their holy Crusade?

The Spanish right understood their situation and were resolved from the beginning

The Spanish right prepared for war with the same degree of commitment and effort as the left

The Spanish right set aside their factional differences before the war had even begun and unified at every turn

You can read a general overview of the lead-up to the Spanish Civil War in my Faction: With the Crusaders Author’s Note. I explain points one and two of the Spanish right’s successes in The Right Prepares for War: the Carlist Requetés. As an understanding of point two requires knowledge of the left’s preparations for war, see my articles The Spanish CNT-FAI Anarchist Defense Cadre Operating Concept and Commercial and Artisanal Hand Grenades of the Spanish Civil War.

In the future, I will write about the Left’s successes and failures in unifying their factions. This article addresses all of the Right’s successes identified above, but focuses primarily upon point 3:

The Spanish right set aside their factional differences before the war had even begun and unified at every turn

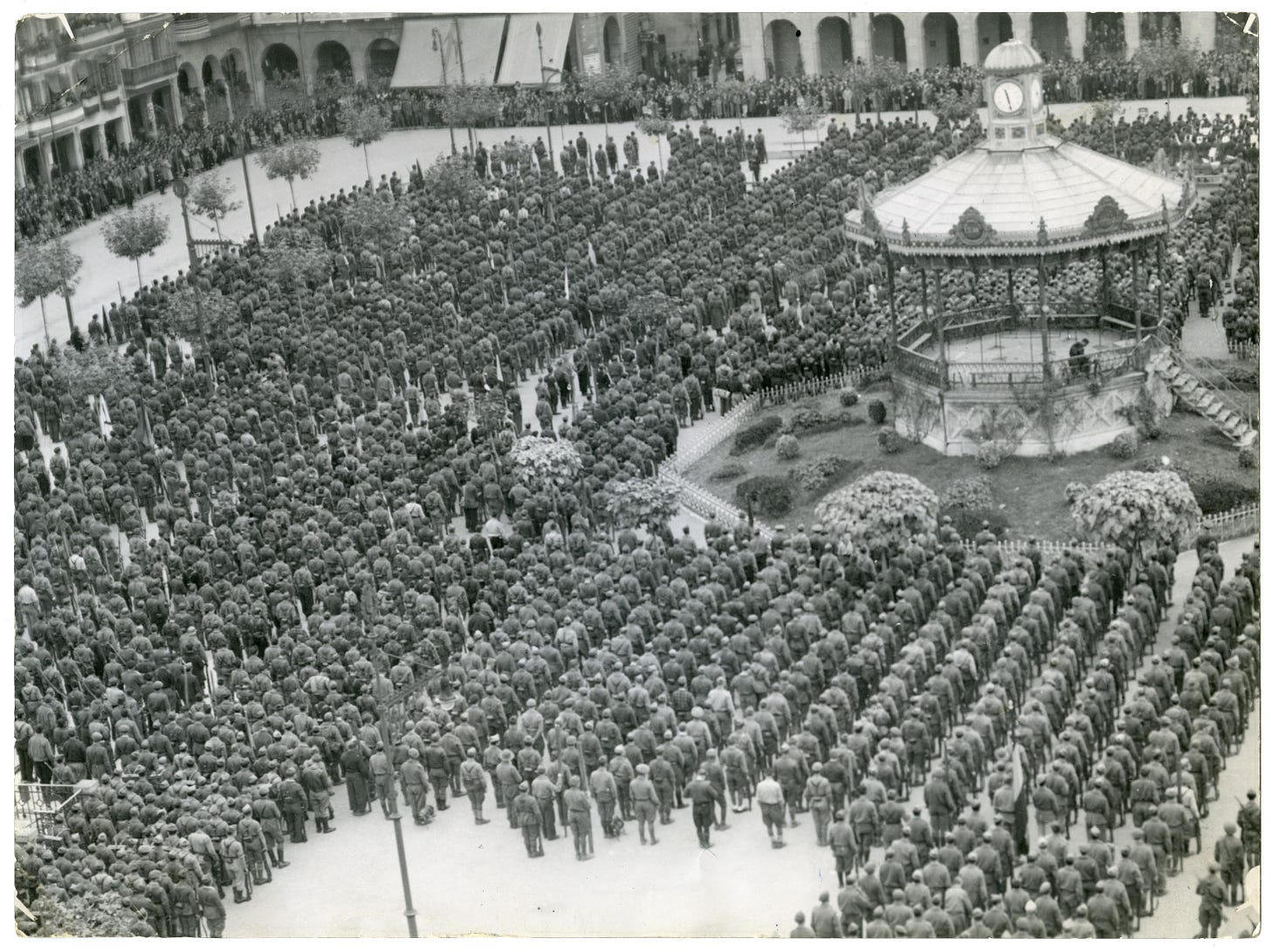

The above image portrays the scene in Pamplona, Navarre, Spain, July 1936, when more than 30,000 men mustered for service in the Plaza del Castillo within the first week of the uprising, with the vast majority joining militias organized by the traditionalist Carlist Requetés, though many also joined third positionist, often described as fascist, Falangist units. These two factions mustered side by side, fought side by side, and their propaganda banners and posters generally coexisted within the Nationalist controlled zone, despite the supposedly important ideological differences between these groups.

Indeed, on April 19, 1937, Nationalist Spain issued Decreto número 255 in Boletín Oficial del Estado, merging the two groups into Spain’s only legal political party, Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista (FET y de las JONS), with General Franco himself as party leader. This became known in Spain as the Decreto, or the Unification Decree. This Decree was read to frontline units on April 21; additional Decrees followed, wherein individuals from the parties were appointed to the party’s executive and the State’s National Council. Standards for the party militias were also defined by Decree, which also allowed for their own symbols to continue to be used until the end of the war. From a military perspective, most importantly, the militias were fully incorporated into the Nationalist Army’s command and logistics structure, which was of tremendous benefit to both the militias as well as the army.

Post-Decreto, Falangist and Carlist units still fought under the command of their own officers and, generally, maintained their pre-existing relationships with the army, such as the Navarre Brigades established before the war between Carlist leaders and the army, particularly the primary leaders of the Nationalist coup plotters, Generals Emilio Mola and José Sanjurjo.

Commentators make much of the wartime reality of political activity having being suspended due to martial law, but I shall demonstrate how the survival of only these two factions from among the many right wing parties of pre-war Spain, which were then unified into a single monolithic Army and State, was completely logical.

The time for politics - petty differences between factions and talk with their enemies - was over

The most “extreme” parties established large, well-organized and relatively well-equipped parallel institutions, specifically militias, which they fielded on day one of the uprising. The future belongs to those who show up

The other rightist faction – the Nationalist officers who had planned the uprising – were either associated with these factions or were apolitical

Before the war, the large, diverse, deeply divided population of Spain had numerous political parties broadly fitting into the “rightist” category. The story of the history of all of these parties is rather long but can be summarized as follows:

Spain’s liberal constitutional monarchy ended in 1931 when King Alfonso XIII abdicated and fled the country. The Alfonsists of that Renovación Española party were traditionalist monarchists who wanted to restore Alfonso XIII to the throne. The party’s leader in the Cortes, José Calvo Sotelo, participated quite openly in both agitation for, and conspiracy in, the eventual military insurrection; the RE sent a group of representatives, along with a Carlist party, to Italy for training and the planning of support for the rising with the blessing of Benito Mussolini. Sotelo was kidnapped and assassinated in July 13, 1936 by members of the Assault Guard, the Republic’s political police, which was the final straw for the Nationalist plotters, who made the decision to launch their coup only a few days later.

The Jaimists, better known as Carlists, of the Comunión Tradicionalista party, were anti-democratic, anti-republican monarchists who had supported the anti-reformist line of the Bourbon dynasty since the succession struggle began in 1833. The individuals, claimants, succession arguments, etc. are far less important than understanding who their supporters were and why they had earned that support. The Carlists preferred their traditional Fueros, the ancient rights and privileges for members of all social classes, local autonomy and a strong Catholic Church, to Libtardism. As explained by Melchor Ferrer in his massive 30-volume history of Spanish Traditionalism, Historia del tradicionalismo español, the principal Carlist tool when striving for political power was the rifle, not a ballot paper. “When competing for parliamentary mandates, the party calibrated its efforts as means of political mobilization and the way to maintain momentum before the next opportunity for a violent overthrow arises.” By 1934, the Comunión Tradicionalista devoted most of its finances to developing and equipping the Requeté militias, who had tens of thousands of armed and trained men ready for action by July 1936. Indeed, the army conspirators determined that, among the Spanish radical groups, only the Requetés had a “genuine citizen army” capable of coordinated tactical military operations.

CEDA, Confederación Española de Derechas Autónomas, or Spanish Confederation of Autonomous Rights, was a political party founded in 1933 from an assemblage of a variety of Catholic conservative parties. Its founder and leader was José María Gil-Robles, who led the party in the elections of November 1933 to the largest number of seats in the Cortes. Much like the left and the Carlists above, CEDA was not a party which participated in parliament for its own merits. In Gil-Robles’ own words, "Democracy is not an end but a means to the conquest of the new state. When the time comes, either parliament submits, or we will eliminate it."

Despite CEDA’s early successes in consolidating the electoral right, after the 1936 elections the moderate, legalistic tones required to maintain the illusion of legitimacy in the Cortes while political violence ramped up caused mass disillusionment among CEDA’s base, particularly their most energetic segment, their youth auxiliary Juventudes de Acción Popular (JAP), who went over en masse to the more radical Falange. Little did they know that, despite his rhetoric, Gil-Robles and leading members of CEDA had been involved in preparation for the military uprising, coordinating some aspects of the plot between military and civilian participants. Gil-Robles also authorized the transfer of 500,000 pesetas of CEDA electoral funds to General Emilio Mola's military insurgents and the nascent Requeté militias yet failed to take the opportunity to feed his own JAP militants into the unit.

The Falange Española, more commonly simply Falange (Phalanx in English), was a third positionist/fascist political party founded by José Antonio Primo de Rivera, whose father, Miguel Primo de Rivera, had led Spain as dictator from 1923-1930. The Falange was a moderated iteration of the young Primo de Rivera’s earlier organization, the Movimiento Español Sindicalista-Fascismo Español, as the previous organization’s pointless ideological positions on the monarchy and the Church attracted few friends and alienated otherwise likely allies on the right. In February 1934, after mutually mediocre performance in the 1933 elections, the Falange merged with Ramiro Ledesma Ramos’ Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional-Sindicalista, another small but equally militant national syndicalist organization which had a base of intellectuals and trade unionists; the new organization’s dedicated core were members of their student organization, the Sindicato Español Universitario. Electorally, the Falange found their greatest appeal among the urban and suburban middle class Spanish deeply disillusioned with electoral politics. In 1934, despite only having a few thousand party members, 83,000 people across Spain voted for Falangist candidates. The party’s real growth in membership came in the lead-up to and beginning of the war, as the Falange’s well-armed militia, the Primera Línea (first line), readily accepted volunteers.

The Falange survived its period of intense persecution after the 1936 elections in part due to adoption of a three-man cell structure, inspired by communist activists, their own flourishing intelligence service, and increased militant activity – indeed, by proactively striking out at leftist agitators, their standing among the anti-communists of Spain grew, although the military conspirators never saw them as much better than assassins or street brawlers.

The Falange and the Carlist Requetés, having established militias and plans of action when the army officers rose up to attempt their coup, were thus ready and waiting for new members who wanted to take up arms against the libtard militants and the Republic. To join the army required a period of training, and control of the various military bases, barracks and armories were somewhat in question for the first few months of the war, particularly July through September 1936, while the militias let you fight libtards NOW.

While much is made of small instances of conflict between these factions during the war, both pre- and post-Decreto, the fact that they didn’t get out of hand and impact the war effort demonstrates the importance the right put upon central authority to mediate, unify and lead their disparate forces to victory. Additionally, the most radical voices within the Carlist and Falangist worlds were snuffed out as a consequence of the war. The most committed ground-level fighters died in huge numbers in the intense fighting of the early war. Carlist General José Sanjurjo died when his small plane crashed upon takeoff from Estoril, Portugal on July 20, 1936, largely due to the excessive luggage the general insisted upon loading the aircraft with, against the pilot’s instructions. General Emilio Mola, The Director of the coup plot and commander of the Army of the North, had become quite fond of the Carlists under his command; he, too, died in a plane crash on June 3, 1937, this time due to bad weather. There has always been speculation that Franco sought to eliminate his rivals, but there is absolutely no evidence of this, and air travel was particularly dangerous in that era. The Falange’s leading voices, José Antonio Primo de Rivera and Ramiro Ledesma Ramos, were arrested (in Primo de Rivera’s case, in the spring of 1936) and executed by agents of the Republic in the early days of the war, though this information was not confirmed publicly for some time. All of these men were made martyrs by their parties as well as General Franco, who well understood the importance of granting people their heroes and symbols, regardless of his own opinions. Indeed, Franco adopted the Falange’s practice of declaring, “¡Presente!” when José Antonio’s name was called at roll call, or when the names of fallen martyrs were read aloud at meetings.

In this (albeit brief) article I've addressed:

Why the Spanish Civil War is worth studying in 2024

What the Spanish right did correctly in order to win, and

How the consolidation of the right's surviving factions into one Army and State was accomplished

If a lesser-known tale from the early 20th century of how the good guys beat the communists rhymes most closely the situation we are faced with in America of the 21st century, what are the key action items we can take away from the study of the Spanish Civil War? For my money, they are:

To recognize our situation and to be resolved to address it head-on. Therefore,

To lawfully legally and peacefully organize and develop parallel institutions which will actually serve us, controlled by, and consisting of, our own people. Key to this organization is the development of natural, logical hierarchies of authority, which is easier said than done. No, this is not an article about muh rugged individualism. Focus, where possible, upon leveraging this into mainstream institutions to serve our own interests, while maintaining the primacy of the parallel institution and the people it serves, and not the mainstream institution.

To worry less about ideological and aesthetic differences between groups, to end the focus upon endless online debate (except in the case of highly persuasive specialists – see the comment about authority above!), and to understand elections as a method of local mobilization and the promotion of those parallel institutions. Passively voting and observing politics as a spectator sport on tha TeeVee is over. And then, when the time is right,

To seek alliances and friendships with other simpatico organizations while primarily concerning ourselves with strengthening our own IRL local groups and parallel institutions. One cannot secure a province without first securing one’s home, then the immediate next block, then the neighborhood, then the town.

May a thousand strategies bloom, and may we all make many frens.

KD

Karl Dahl is the author of Faction: With the Crusaders.

I also take very seriously Matt Bracken’s “Yugoslavia times Rwanda” formulation