The Right Prepares for War: the Carlist Requetés

More Organizational Lessons from the Spanish Civil War

In July of 1936, Spanish military officers rose up with the intent to overthrow the Republican government of Spain, which they considered illegitimate due to both rising chaos and the anti-tradition bent of most Republican factions, in a coup d’état. The coup faltered due to the uprising’s failure to secure much of the country, in large part due to the mobilization of anarchist and socialist militias. So began the Spanish Civil War.

There are many high-quality English language sources where one can read about the military conspiracy and events in this period; let us instead delve into a critical but oft-glossed-over subject, the organization of the Carlist Requeté militias, who seized and held a critical portion of Spain and without whom the Nationalist effort surely would have failed.

Famed Basque General Tomas Zumalacárregui of the First Carlist War dubbed Navarre’s Third Battalion of volunteers “The Requeté”. Interestingly, “requeté” does not seem to be a word of Spanish origin; Spanish sources state that it is of Navarrese origin, probably from the French language. Navarre has a deep history with neighboring France, having been a part of that kingdom, on and off, up through the French Revolution, under the House of Bourbon, beneath whose banner the Carlists fought. Consider also that Basque Country extends through Navarre into France, and both conservative Spain and progressive France imposed their national linguas franca in schools and official use, so it’s no surprise that Zumalacárregui was familiar with the French language.

There are two common theories in English as forwarded by Carlist historians as to Zumalacárregui’s coinage: first, it is a reference to the buglers’ requête de chasse, or hunting call, used by the mounted troops to coordinate their movements; alternatively, Zumalacárregui is said to have used a Navarrese colloquialism, which then became a part of the Spanish language, when asked about the performance of his various forces in the First Carlist War: "todos muy bien, pero los navarros requetebién" – “everyone was very good, but the Navarrese were excellent.”

The truth, as well-documented by Navarrese historian José María Iribarren in his piece Sentido y Origen de la Voz "Requeté" (The Meaning and Origin of the Word "Requeté"), is that the Third Battalion of Navarre, Zumalacárregui’s favorite of his battalions, were uniquely named “the Requeté” due to a “peculiar” song they sang, which self-consciously made fun of their ragged, impoverished state and relative nakedness. French, English and Spanish sources reinforce Iribarren’s argument, and provide the following lyrics, translated to French, then English:

Vamos andando, tápate,

que se te ve el requeté.

("Allons, marchons, couvre-toi, car Ton voit ta... nudité").

(“Come on, cover yourself, your Requeté is visible.”)

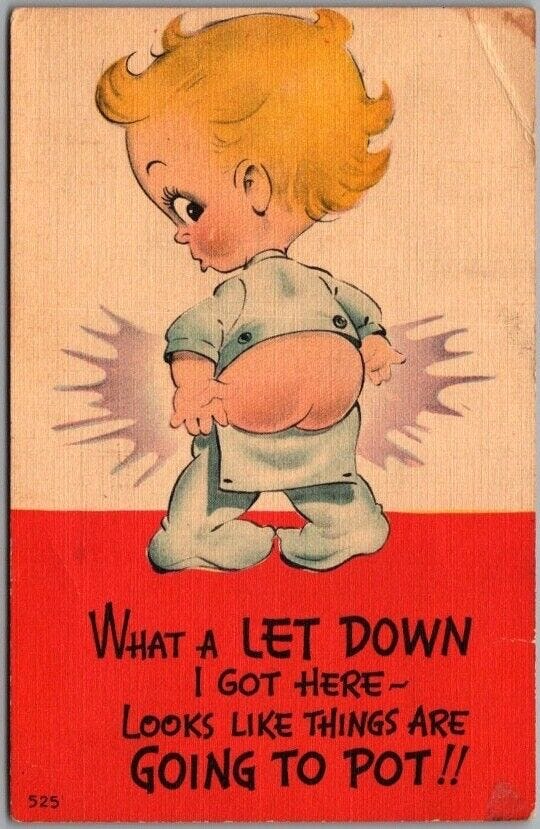

Iribarren quotes Navarrese historian José María Azcona: "The indeterminate meaning of this word [Requeté] gave it a certain malicia inocente [literally: innocent malice, though this author would say for a modern, Anglophone audience, playful naughtiness] and encouraged the childish mischief of the soldiers." Devout Catholics, profanity or transparent ribaldry wouldn’t have been tolerated, so they substituted a rhyming nonsense word, what IIribarren calls “un tururú, tararí or tralala” borrowed from another language with no established meaning in Spanish. The origin of the reference to nakedness, then - again quoting Iribarren: “There is no doubt that the word requeté was trying to refer to "what was seen" through tears or slits the pants. Now, were these tears caused by wear and tear in the butt area, or were they due to the slit called the gatera?”

The gatera is a buttoned “port” which we all recognize from childrens’ pajamas as pictured in vintage cartoons, which Zumalacárregui mandated be included in the humble trousers of his Navarrese guerrilla fighters to allow them to handle their business unincumbered, minimizing that dangerous time so vulnerable to bushwhacking?

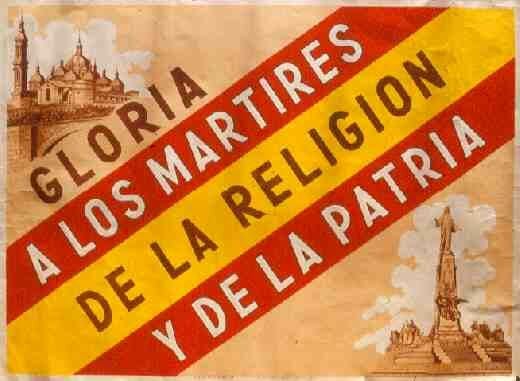

Coinage aside, “Requeté” went on to be the name used for traditionalist Catholic volunteers under the flag of the Bourbons, both individually and as a collective in the Second and Third Carlist Wars as well as the Spanish Civil War. In extreme shorthand, each war came about through the failure of political maneuvering to establish a system that balanced tradition with liberalism; it is no exaggeration to state that the liberals attempted to legislate away the Church and regional legal structures and traditions as in neighboring France, which of course was implemented via violence. The traditionalist Catholics of Spain were well aware of France’s Reign of Terror and the atrocities committed in the Vendée; the victimization of the Spanish by the French – and the English – between 1808 and 1814, as well as their courageous resistance, was a fresh memory. As Plutarch attributed to Pompey, “Will you not give up reading laws to us men girt with swords?”

If not honestly conducted, they produce the victory of fraud; if they are honestly conducted, they normally bring about the triumph of cultural inferiority – that is, of the majority.”

- Carlist politician Luis Hernando de Larramendi y Ruiz on elections

Carlism took on a political and cultural character in peacetime, particularly after Isabella II and her faction were expelled in the Glorious Revolution of 1868; though they had representation in parliament, the movement’s character was primarily regional, centered upon local assemblies and their social action programs. Carlists played key roles in the establishment of Catholic Labor Unions to counter the leftist trade unions. The Requeté name reappeared in casual use at the turn of the century in youth formations associated with local Carlist assemblies, such as the Juventud Carlista; the urban groups became increasingly independent and radical in the “very cool, skilled and masculine” sense as used by 1980s skaters, fighting in the streets against anarchists and communists. Radical!

While the second half of the 20th century saw subversive outsider media glamorize rebellion against tradition as romantic and high status, the Carlist youth, who were part of actual communities where deference flowed upward, respect downward, believed the opposite – protection of their families, communities, Faith and traditions was cool – protecting the Church and securing public spaces against their enemies. A traditionalist Catalan language paper, La Bandera Regional (“The Regional Flag”), is said to have published the first explicit reference to a youth Requeté unit in their October 1908 edition, citing el “Requeté te Carli de Manresa,” the Carlist Requeté of Manresa,” a Catalan town on the Mediterranean coast.

The Carlist Requeté of Manresa has agreed to take the stage and to collaborate with the traditionalist press, considering that this is today the strongest and most appropriate weapon with which to fight against liberalism and to spread good doctrines everywhere….

Carlist youths of Catalonia: assist as you can via our press. Let's spread propaganda, we who can't do anything else; those who feel the vocation, contribute with your pen; help those who can't contribute anything else to the best of your ability. Thus, our press will flourish, and we will bear fruit and win adherents to our Cause.

Then at the sight of our august leader [Don Carlos de Bourbon], as if by magic, a legion of future heroes, future soldiers, will arise who will know how to fight bravely and enthusiastically, dying if necessary, so that our dear Spain may escape from the grasp of the liberal monster.

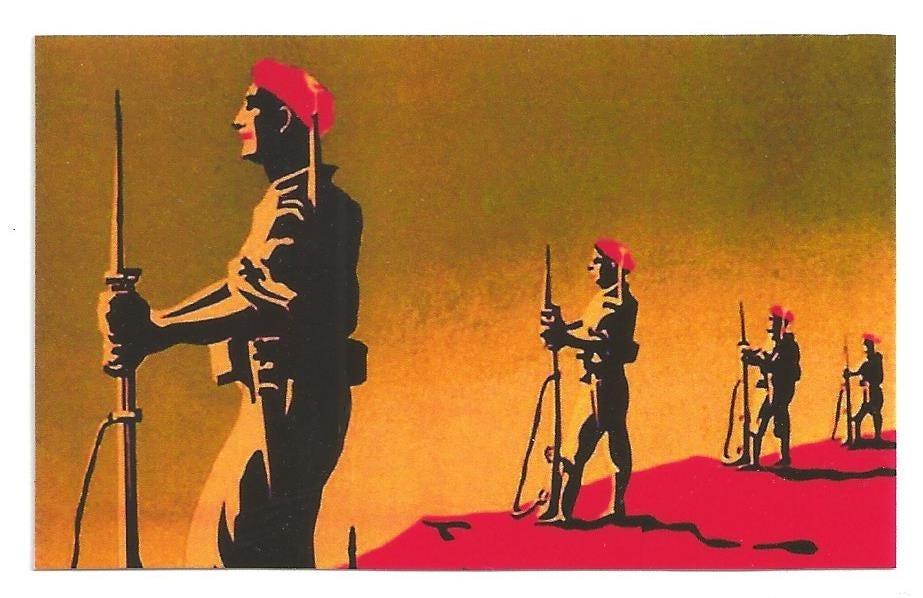

Readers in The Current Year Plus Whatever should understand well the value of youthful energy in the creation of propaganda; imbuing it with a sense of identity, belonging and respect, cultivating and strengthening young men to prepare for not just life, but inevitable war; think “explicitly militant scouting.” The Requetés and Juventud Carlista, the Carlist organization for young men, eventually developed a formal relationship, the former led by and feeding into the latter as members reached 16 or 17. The Requetés wore their traditional red berets as their primary uniform and participated in Church events, charity, sports, outdoor activities, drill, music and other cultural development, marching with Carlist organizations, and propaganda – selling party periodicals, distributing pamphlets, leafleting, and tearing down Red posters and banners. They had their own guidebooks and training manuals, and could, of course, use the materials of other youth organizations to guide them in other activities.

The libtard press, of course, blamed the Requetés for incidences of political street violence, while Carlist organs portrayed the Requetés as preventing damage to churches or protecting peaceful participants in Carlist rallies and marches. Street violence at the time is reported to have consisted primarily of fist fights, frequent use of melee weapons, and the occasional employment of firearms, including an innovative 1915 drive-by shooting ascribed to the Requetés.

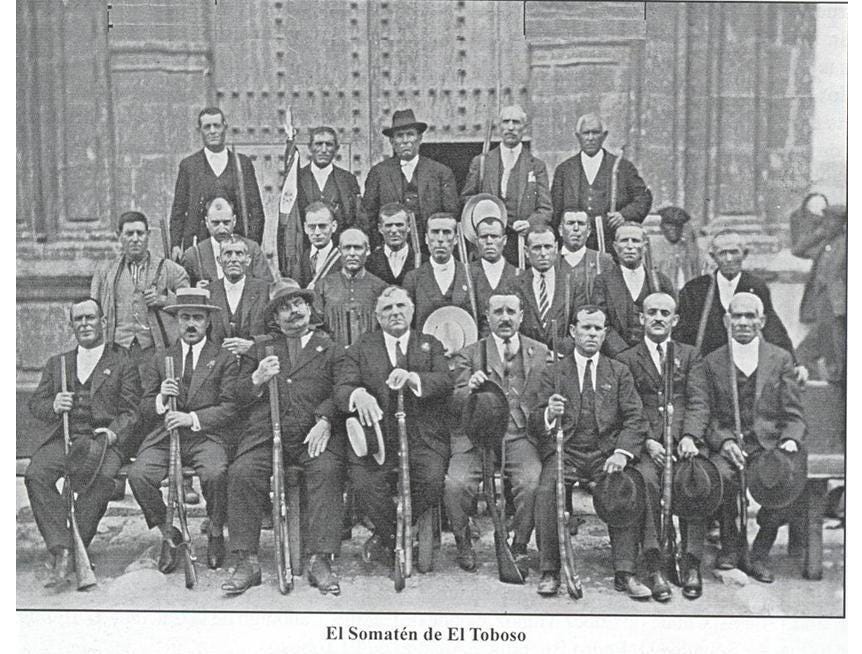

In 1913 the Carlist organization, at the behest of Don Jaime, reorganized their youth organizations along the lines of a French monarchist group, the Camelots du Roi, and made the Requetés an official party branch under the Junta Superior Central. There were plans to adopt military-style uniforms and structure, which may or may not have taken place, but law enforcement was cracking down on explicit public representation of paramilitary organizations. In that period the Carlist movement stalled and went through various reorganizations, with a substantial portion of participants leaving for less militant mainstream Traditionalist parties. The dictatorship of Primo de Rivera, which began in 1923, cracked down on surging political violence, particularly in Catalonia, which quieted militant both leftist and Carlist union and Requeté activity, pushing it underground. No small number of Requetés joined the Somatén, a recently revitalized, officially-sanctioned Catalan citizen militia with ancient roots, at the urging of the Marqués de Villores, a young Carlist politician who had earned the favor of Don Jaime. Soon, the president of the Barcelona Requeté, Felix Oliveras y Cots, was arrested, along with others, under suspicion of plotting a coup; the party executive snuffed any embers of pro-coup sentiment.

The Primo de Rivera regime fell in 1930; in May of that year, Don Jaime ordered the Carlist leadership to Paris, where they established the Comité de Acción, the Action Committee. In the early summer of 1931, the Comité de Acción set out to re-form the Requeté as an adult paramilitary organization, centered in their Navarre and Basque Country strongholds, to be trained and commanded by professional military men. Retired Colonel Eugenio Sanz de Lerín was appointed lead instructor of the Navarre Requeté while his two primary field commanders recruited from the local Requeté youth organizations, Generoso Huarte and Jaime del Burgo, set out on a propaganda and recruiting campaign with the aid of five parish priests who focused upon winning over the local clergy. By August, the dormant Carlist movement had reawakened around “the religious issue,” as the Republicans dismissively referred to their planned Constitution’s explicit intent to crush the Church in Spain; the network numbered several thousand men, organized in ten-man units known as decurias, after the Roman formation. The networks’ goal at the time was to establish small, local, independent units for the protection of religious institutions. By the end of the year, their number had at least tripled, perhaps growing to up to ten thousand men. Arms, however, were few and far between. Republican press organs bleated in terror over reports from local libtards regarding the rebirth of the organization; Martin Blinkhorn asserts in Carlism and Crisis in Spain, 1931-1939 that one of the loudest voices was Indalecio Prieto, the Republic’s obese Finance Minister and a Basque member of the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (Partido Socialista Obrero Español - PSOE).

The corpulent Prieto seems to have been especially terrified of his ancestral peoples’ spirit, and believed, in a historic irony, that the Basque-Navarre Country autonomy campaign then underway to be a mere front for “sedition by Alfonsists [royalists loyal to deposed King Alfonso XII], Jaimists [Carlists], Nationalists and Jesuits” against the Republic. In response to these claims, on August 20, 1931, the Republic shut down nearly all Catholic newspapers in northern Spain, as well as other conservative newspapers elsewhere; they arrested more than a few right-wing newspaper owners for publishing “intemperate” editorials.

The Carlist claimant to the Spanish throne, Don Jaime, died in October 1931; he was succeeded by Alfonso Carlos de Borbón, 82 years of age. In late 1931, violence spiraled out of control thanks to CNT-coordinated strikes and political attacks. In December 1931 the Republic’s anti-Catholic Constitution was approved, along with the Law for the Defense of the Republic, enabling legislation which gave great power to Minister of Governance (Interior) Santiago Casares y Quiroga, a radical Republican and atheist.

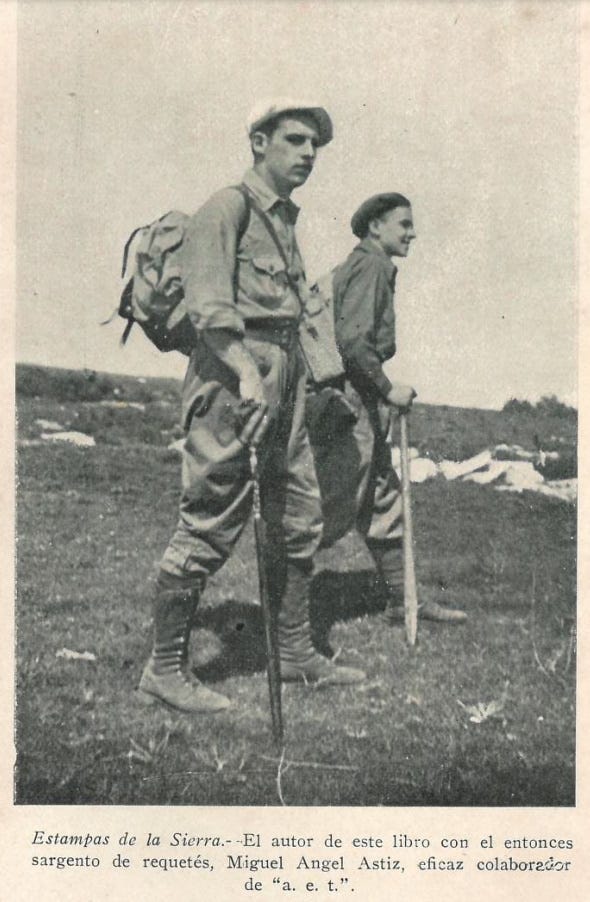

With the failure of the Basque-Navarre autonomy statute over disagreements between heterosexuals and others regarding the centrality of Christianity, in 1932 the Carlists formed a new party, the Comunión Tradicionalista, which directly confronted the Republic in the Cortes and in the realm of public opinion. The training and militarization of the Navarre Requetés intensified as the tense political environment led to increased street confrontations; Carlist plotters began to focus upon acquisition of arms and equipment with the financial support of the party. Jaime del Burgo Torres, a key Navarre Requeté field commander, was not a military veteran; he grew up in the youth Requeté organization, rose to secretary of the Navarrese Juventud Jaimista, and leveraged his position in the new national Carlist youth organization Agrupación Escolar Tradicionalista, to network and acquire and distribute weaponry, primarily handguns from Eibar, with and without official party sanction. Following armed clashes between AET and UGT militants in which two UGT members and a Carlist died and four other participants were seriously injured, he was arrested and charged with, among other things, trafficking arms, which he had done, but the state could not prove it! At age nineteen, after six months in prison, he was acquitted and released. The timing of his release was fortuitous for the Carlist cause, as the August 1932 Sanjourjada, the abortive Carlist coup under General Sanjourjo, resulted in the rounding up of many of their conspirators, including the Requetés’ lead trainer Colonel Sanz de Lerín.

In his largely-autobiographical historical work, Requetés en Navarra Antes del Alzamiento (Navarre Requetés Before the Uprising), del Burgo details his activities under the new, more strictly military organizational structure of José Enrique Varela, a “mustang” who had enlisted as a Spanish Marine, then later enrolled in the infantry school and graduated as a lieutenant. A decorated veteran of decades of war in Morocco, including with Franco’s Legion, Varela was twice awarded the Laureate Cross of Saint Ferdinand, Spain's highest military award for gallantry. In the first days of the Republic he participated in a military mission which traveled about Europe to broaden the Spanish army’s military knowledge. Also a participant in the Sanjourjada, it is not clear why he was released from prison so soon and thus able to participate in the conspiracy, coordinating both within the military as well as the Carlist’s own militia activities. Varela traveled undercover, disguised as the priest “Don Pepe,” and spread the Requetés beyond Navarre into Catalonia, Aragon and Basque Country.

[Note: your correspondent is sorely tempted to translate Requetés en Navarra Antes del Alzamiento into English, thanks to the following libtard endorsement: “This is a terrorist's manual on an ideological level. To complete it fully, an appendix dedicated to how to build hand grenades would have been useful.”]

As the Requetés grew, Varela reorganized the Requeté units, moving from individual ten-man decurias into a variation on the standard Spanish infantry structure – six-man patrols (patrullas), one of them a corporal in charge; 3 patrols form a 20-man platoon (pelotón), two of them sergeants; 3 platoons form a 70-man picket (piqueté); 3 pickets form a 246-man requeté; 3 requetés form a 720-man tercio, the old Spanish infantry “third,” roughly a battalion. The leadership and activists began to go to great lengths to acquire infantry weapons with financial backing by the Comunión Tradicionalista. The bulk of weapons acquisitions appear to have begun in 1934, aided by Carlist businessmen and politician José Luis de Oriol y Urigüen, who, in one case, arranged for the charter of a ship and the purchase from Belgian sources of 6,000 rifles, 150 heavy machine guns, 300 light machine guns, 5 million cartridges and 10,000 hand grenades. All the arms were detained in port by Belgian law enforcement, but the Requetés took possession of the machine guns. The King of Belgium eventually personally intervened to lift the embargo against the Carlists, but too late for the rising.

Don Antonio Lizarza Iribarren, a Carlist conspirator who spent time imprisoned in Madrid just before the rising, writes in his memoir “Memorias de la Conspiración 1931-1936” (“Memories of the Conspiracy 1931-1936”) that one of the more successful weapons acquisitions was of 1,000 Mauser C96 “Broomhandle” pistols with wooden buttstocks as well as ammunition, delivered at the French border and subsequently hidden in various locations around Pamplona. It seems that vast numbers of handguns, Broomhandles and rifles made their way to the Carlist conspirators from France via old routes in the French Basque Country, where they were smuggled or possibly brought over the border with a wink and a nod. The weapons were often hidden in wine barrels, disguised as part of the normal trade between the two countries. In one specific case Lizarza tells of arms from Eibar, restricted by law for export only, which were consigned for shipment to a complicit arms dealer in Belgium. At the same time, Lizarza’s friend and co-conspirator Agustín Tellería made a large purchase of household hardware in Eibar to be delivered to Pamplona. The shipping labels were given the ol’ switcheroo and the hardware went to Belgium while 17 crates of rifles and handguns went the Requetés for safekeeping. Thousands of handguns made their way, in large and small batches, to the various Requetés through the actions of primarily older supporters, businessmen and senior community members who could justify to the Republic’s security apparatus the possession of large amounts of cash as well as extensive travel.

“And so, hundreds of cases.... How many trips were made back then! Exposing ourselves in each of them, and even though we were in very compromised situations, we always got ahead with the help of God.

“Each town in Navarra has its own little story in this matter of weapons. Each has its adventures, and dangers. Many were reached; for others it was not possible. There were more hands than weapons.”

- Antonio Lizarza Iribarren

By mid-1935 “Don Pepe” Varela was under such close scrutiny by the Republic that he was recalled to active duty as a way of controlling his activities; he handed over his role as Inspector General of the Requetés to retired Teniente Coronel Ricardo Rada Peral, a seasoned veteran of the Moroccan campaigns in the Spanish army as well as the Legion, who had also participated in the development of the Falange’s militia organization as well as the Unión Militar Española, a secret society within the army working between the various rightist factions to prepare for the overthrow of the Republic. By the spring of 1936, the Requetés had ten thousand fully armed and trained men, with twenty thousand auxiliaries, across Spain; in the assessment of the seasoned military conspirators, the Requetés had the only “genuine citizen army” capable of coordinated tactical military operations, unlike the other parties, whose militant wings could only field “street fighters and assassins.”

In yet another tremendous irony, the Popular Front government, “elected” in February 1936, shipped General Emilio Mola y Vidal, one of the chief plotters of the military conspiracy, to “backwater” Pamplona, where he was made commander of the city’s garrison. Libtards, as ideologues, were, as they still are, incapable of humanizing their opponents or entertaining logically how they intellectually and emotionally interact with the world. After all, Mola worked for the deposed king Alfonso XIII, whom the Carlists hated on paper! The notion that the various right factions could work together and compromise to accomplish greater aims, rather than plot to eventually stab each other in the back like the Republicans, simply didn’t occur to their pea brains. [Note: this is not an entreaty to underestimate your opponents]

Mola announced the Nationalist coup on July 19, two days after the rising in Morocco and a day after the previously agreed upon date; a state of war was declared in Pamplona. The army and Requetés seized the city, the rest of Navarre and the border with France within a few days. Many Basque Carlists, Requeté or otherwise, overwhelmed by the alliance of leftists, Republican-aligned Basque nationalists and Republican forces, fled Basque Country to Álava or Navarre to escape with their lives as well as to shore up the local Carlist units . Carlist forces in Aragon called for aid against a rising of leftist militias; the Navarrese responded and helped capture much of western Aragon, while other Navarrese units plus those from Castile, Leon and Galicia failed to reach Madrid but successfully secured the northern border of the Sierra de Guadarrama and enclosed the Basque Country. Furthermore, Requetés were critical to the establishment of a toehold in southwestern Andalusia as well as securing Seville and Cordoba.

The front, Spanish Civil War, July 1936:

Indalecio Prieto remarked, perhaps typical of the libtard faction, that the enemy he feared most was "a requeté who has just received communion.”

Note: in addition to the works cited above, the very best source online for information about the Carlist Requetés and their history is www.requetes.com. Use translation software - don’t be shy! ¡Lo demandó el honor y obedecieron; lo requirió el deber y lo acataron! “Honor demanded and they obeyed; duty called and they complied!”

Great article.

For a more generalist perspective on the S CW:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vBftWGlIWvU&list=PL2Ms3UVVn-WzQZrIyhmBYwKls1B7v6Yhj

The most useful information I got from it was the interviews they did of the communists. They are 70+ years old, and mindless fanaticism still shines out of their eyes. You cannot reason with these people, and making a deal with them only gives them time to get the strength to strike again. And again, and again.

Excellent read! Surpassingly few Americans know anything AT ALL about the Spanish Civil War, one of the most fascinating subjects around.