WARNING

Don’t get any silly ideas - the information contained herein is for historic and informational purposes only. The author and publisher disclaim any liability from any damages or injuries of any type that a reader or user of information contained within this article may encounter from the use of said information. There are federal, state and/or local laws which prohibit the possession and/or manufacture of the devices described. There are no secret formulas or special information contained within this article that cannot be found in a Wiki article. Comprehensive documentation regarding commercial and hobbyist pyrotechnic production processes and formulas, safety practices, etc. are available online – what follows is merely a high-level summary with the occasional teasing detail. Don’t be naughty and don’t blow your hand off like a silly goose. To reiterate, the author and publisher disavow bad things and hurt feelings.

“[A]ges in which the dominant weapon is expensive or difficult to make will tend to be ages of despotism, whereas when the dominant weapon is cheap and simple, the common people have a chance. Thus, for example, tanks, battleships and bombing planes are inherently tyrannical weapons, while rifles, muskets, long-bows and hand grenades are inherently democratic weapons. A complex weapon makes the strong stronger, while a simple weapon – so long as there is no answer to it – gives claws to the weak.” – George Orwell, You and the Atom Bomb

One fascinating aspect of the Spanish Civil War is the distinct manner in which the entirety of Spanish society, in both the Nationalist and Republican Zones, became organized around the war. This included a level of military industrialization rarely addressed in the few English-language sources about the war, as both sides lacked sufficient equipment needed for modern war as established during World War One, not to mention the new age of mobile warfare of which this war was a harbinger. A curious element of this militarization was the local and factional development of hand grenades, as some sides in the war already came to the fight with their own hand grenades, referred to in the Spanish as “artisanal,” which has the same definition as in modern-day English – boutique, small batch, locally-sourced, and hand-crafted with love by skilled artisans.

As of November 2023, the very best source regarding the depth and breadth of Spanish Civil War arms is the website www.amonio.es, a treasure trove of Spanish-language armaments research that you can’t find anywhere else. These anons cracked the code on the origin and iterations of the infamous FAI bomb! If you don’t read Spanish, use your preferred free online translation software; if the output doesn’t seem correct, look up individual words or phrases with online dictionaries as machine translation often fails with technical terms. The amount of work done by these collectors, amateur archeologists and autists – please interpret this author’s word choice in the loving spirit which is intended – is truly impressive and deserves a great deal of credit.

Broadly, anti-personnel hand grenades typically fit into two classes: defensive and offensive. An offensive grenade relies upon its explosive blast, not fragmentation, and is thus less likely harm the man who throws it as they assault into the same position due to their construction – light sheet metal or, now, polymers. Defensive grenades, intended to be thrown from behind cover, kill in a larger blast radius due to fragmentation effects caused by the construction of their bodies – usually segmented sand-cast iron or containing pre-fragmented materials. The famous German “potato masher” stick grenade was an offensive type, its sheet metal body creating relatively little fragmentation; its wooden handle allowed it to be thrown for further distances due to leverage. The archetypical American and British “pineapple grenade” and Mills bomb, respectively, were defensive fragmentation grenades. A key danger of fragmentation grenades is that their lethal radius is often greater than the distance even a competent thrower can throw them, hence their doctrinal “defensive” employment from behind cover.

As important in the effectiveness of such weapons is the explosive material used – black powder, for example, bursts at a relatively low pressure and lacks “brisance,” the shattering or crushing effect of an explosive caused by a high rate of detonation which marks the difference between low and high explosives. One of the more common high explosive mixtures used in Spain is known as ammonal, a mixture of ammonium nitrate (the oxidizer) and aluminum powder (the fuel), a much less expensive and more easily obtained material than TNT; different materials are added to stabilize the material, make it more easily detonated, or to increase brisance. The Spanish military preferred a mixture known as T-ammonal for their grenades and mortar rounds which consisted of 58.6% ammonium nitrate, 21% aluminum powder, 2.4% charcoal and 18% TNT. A legal, non-regulated, patented variation on this mix, sold as a binary product mixed by the end user, has been quite popular in the United States since 1996 for use in explosive rifle targets due to sensitizers added for that purpose.

Common Hand Grenade Fuses of the Spanish Civil War

Grenade fuses are more varied than most members of the public are aware of, though the oldest fuse type, wicks lit by open flame, persisted in military use well into the 20th century in much of the world. The Spanish “Tonelete n 1 de guerra,” a small, handy exposed-fuse cast-iron fragmentation grenade remained in military issue through much of the war on both sides; it had a crimped sheet metal fuse cover to protect it from the weather and its wick was bound in wire and impregnated with wax to make it both relatively easy to use and weatherproof. This was also a popular style of fuse utilized by the Republican militias in their craft grenade works as it was simple and reliable, if not as easy to use in combat as more modern mechanical fuses. There are numerous photographs from the war of Republicans using grenades which appear to be no more sophisticated than large food tins stuffed with gunpowder. The most common booster charge for all fuses, including wick fuses, was, and still is, mercury fulminate, the (very dangerous!) recipe for which can be found in many fine locations online, though the author cautions the reader against investigating beyond the purely theoretical as the reader most assuredly lacks the appropriate safety equipment and licensing to do so. Don’t be a silly goose!

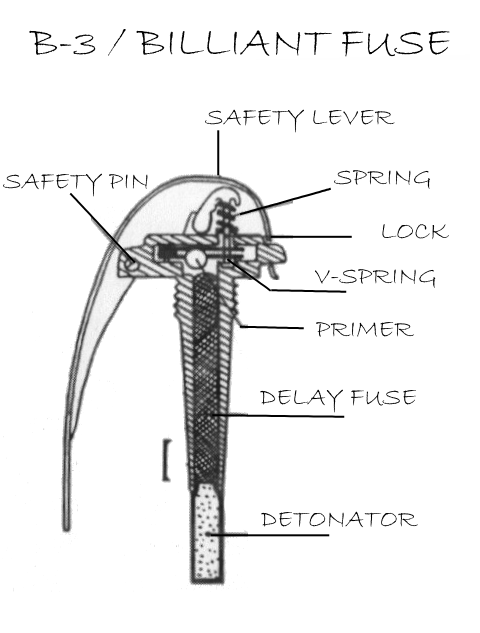

The most common type of mechanical grenade fuse used during the war was the striker-fired percussion type, either a delay fuse or a zero-delay impact fuse. This type is best illustrated by the classic American Mk. 2 “pineapple,” British Mills bomb, French F1, Soviet UZRG, Spanish Republican B-3 copied from the French Billiant fuse, or Polish wz.GR.31. The American, B-3, French Billiant and Polish wz.GR.31 fuses have pivoting strikers while the Mills, UZRG, and the French F1 fuse use in-line coil spring powered strikers. The French Billiant fuse was issued with their F1 grenade issued to WWI American expeditionary forces.

Inertial striker-fired impact fuses were extremely common in grenades used in the Spanish Civil War, particularly the Spanish army’s Lafitte grenade, the CNT-FAI’s “FAI bomb,” and a variety of more sophisticated Italian grenades – the SRCM Mod. 35, OTO Mod. 35 and the Breda Mod. 35. The CNT-FAI’s “FAI bomb” is the only “defensive” or fragmenting impact-detonating hand grenade in this class used in substantial numbers during the war, with the others all being of the offensive type, but it’s entirely possible that there are obscure, hand-crafted or improvised exceptions that we have not seen documented.

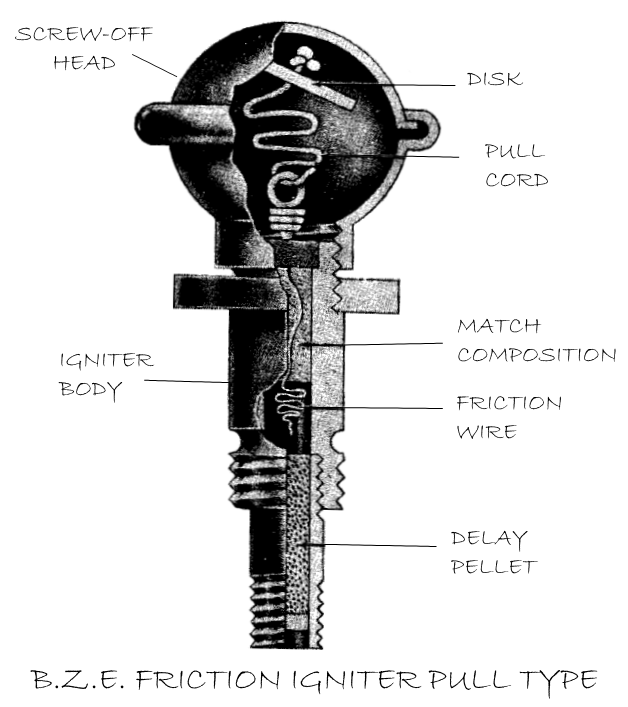

The final fuse type commonly seen in Spain was the German friction igniter type, almost entirely in the B.Z. 24 and B.Z. 39 fuses as used in the Stielhandgranate, the classic “potato masher” or “stick” grenade, an offensive grenade used by both the Condor Legion and Nationalist forces. Sources allege that either pre-adoption or prototype examples of the Model 39 Eihandgranate, also an offensive grenade with a thin pressed steel body using the B.Z.E. friction fuse, were employed in the closing days of the Civil War. In the B.Z. fuses, a tube of lead contains the copper ignition capsule, inside of which is a potassium chlorate-charcoal-dextrin friction ignition composition cast around a twisted friction wire coated in a shellac-alcohol-phosphorus mix, sometimes called a “match composition,” as the mix is essentially the same as found on a self-lighting match head. A pull cord secured to the pull wire hangs out one end of the tube, which is crimped to retain the ignition capsule. The other end of the lead tube is crimped around a soft metal tube containing a black powder delay pellet; this assembly is screwed into another containing a tetryl detonator. In the Stielhandgranate, the pull cord is tied to a grooved porcelain ball, which is concealed in the hollow wooden handle and accessed by unscrewing a cap on the end of the handle. The pull cord on a B.Z.E. friction fuse, as found on the Eihandgranate, is contained in the hollow knob atop the fuse, which is unthreaded from the detonator housing.

The B.Z.E. fuse’s cap was color-coded to indicate the length of the delay pellet so that users could employ an appropriate fuse:

· Yellow – 7.5 seconds (magnetic shaped charge)

· Blue – 4.5 seconds (standard issue)

· Red – 1 seconds (smoke)

· Grey – no delay (booby-traps and demolition work)

The FAI Bomb – the C.N.T.-F.A.I.’s Secret Weapon

How is it that “impromptu” workers’ militias came to fight the sudden military uprising in July 1936 with huge numbers of craft-made hand grenades?

"In the absence of preparation, there is no revolution—and the more intense and shrewder the preparations, the more the revolution will prosper when the day comes." So stated an internal document of the anarchist C.N.T.-F.A.I., who learned from prior failed revolts and general strikes that "improvisation and hot-headed schemes" - spontaneous uprisings - didn't work and that they had to organize. Their revolutionary preparation included the development and mass production of a hellish fragmentation grenade with which 20,000 CNT fighters secured Barcelona in a matter of days.

George Orwell refers to the "FAI bomb" in his Homage to Catalonia, one of only a handful of English-language memoirs of the Spanish Civil War. It was known to the Spanish as "la imparcial," The Impartial, for its sketchy fuse and a wider lethal radius than it could be thrown. The one-kilo (2.2 lb) bomb's safeties were a cloth streamer wrapped around the body as well as a safety pin that retained the safety lever. The user would loosen the streamer, pull the pin, and throw grenade; the streamer would deploy and orient the spring-loaded striker to the target.

The FAI bomb was very dangerous, but for packs of anarchist butchers it was just the ticket for street fighting. It was used widely in Catalonia, on the Aragon front and around Madrid, and was manufactured by the FAI and the War Industry of Catalonia until late 1937 when it was replaced by a smaller, handier grenade using a copy of the Billiant striker-fired delay fuse.

When the Durruti Column left the Aragon front in November 1936 to support the Republican government's defense of Madrid it's said that they brought 35,000 FAI bombs; it's likely that they were already being produced in the collectivized Catalonian factories. Manufacturing blueprints for the FAI bomb survive thanks to the War Industry of Catalonia.

Where did this bizarre design come from? Per Memorias: 1897-1936, the memoir of Spanish-Argentine anarchist Diego Abad de Santillán, born Sinesio Baudilio García Fernández, in 1931 he approached aviator Ramón Franco, General Francisco Franco's brother, to acquire a small aviation bomb for "study." Ramón Franco was known to have traveled in anti-monarchist circles. "The Abbot of Santillán" claims that Ramón commissioned an Asturian expert to make a model of a fragmentation grenade that would make the Spanish army's Lafitte grenade "appear as a toy." In the wake of the 1930 Argentine military coup, "The Abbot" lived in exile in Uruguay after receiving a death sentence for sedition; he was in Spain in 1931 to attend a CNT conference when he committed himself to develop the grenade.

Back in South America his compatriot Simón Radowitzky and an Italian anarchist by the name of Antonio Destro developed the production model. Radowitzky, Destro and "The Abbot" built over one thousand of "Ramón's hand bombs" in both Uruguay and Argentina in preparation for an aborted coup in Argentina; lead bomb-maker Raúl Guillermo Luzuriaga was maimed in an accident while assembling bombs and thus narrated the assembly process to assistants. Argentinean police captured Luzuriaga, another conspirator, and the bomb works in December 1932; "The Abbot" reappeared in Barcelona in 1934 where he founded an anarchist newspaper, "Tierra y Libertad," and became a leader in the militant FAI clandestine group.

The FAI leadership decided to fully commit resources to mass production of the FAI bomb, the cost of which irritated less militant CNT leader Ángel Pestaña greatly, as FAI funds came from CNT dues. As had become traditional, in 1935 the FAI’s lead bomb maker, “Braulio” Victoriano Prieto Robles, blew himself to pieces while testing FAI bombs in the remote hills of Collserola Park northwest of Barcelona; his comrades buried him in secret. What a silly goose!

“Abbot Diego” served as the Minister of Economy in the Revolutionary Catalan government (in the great Antoni Gaudí’s Casa Milà) from December 17, 1936 through April 3, 1937 and was certainly involved in establishing production of the FAI bomb at War Industry of Catalonia facilities. He acted, later regretfully, as a leading voice to pacify the anarchists of Catalonia in the “May Days,” the May 1937 street battles in Barcelona, where the communist leadership of the Republic ultimately crushed the independent anarchist and socialist parties. George Orwell’s sponsors in the POUM were annihilated and CNT forces gelded and absorbed into the communist-run army. Cowed, “Abbot Diego” wrote After the Revolution in protest, a book about ideas, specifically Pure Land Anarcho-Syndicalism, and the good vibes denied the world. The communists never pressed the muzzle of an Astra pistol, or a Soviet Nagant revolver, against the back of his head because they didn’t need to. LOL; LMAO, even. In exile postwar, he went on to write Why We Lost the War, which placed the blame for Franco’s victory squarely upon external forces: the Republican government’s sell-out to, or takeover by, the Soviets, and the failure of the liberal democracies to openly come to the assistance of the Republic that didn’t actually care about Republican values. Thanks for the history of the FAI bomb, dude.

The “Tonelete” and Its Many Copies

In 1918 the Spanish Army adopted the n 1 model grenade, a simple defensive hand grenade of cast iron with a nearly foolproof fuse – a safety fuse or wick, recorded in Spanish manuals as the Bickford fuse to credit its inventor. A core of gunpowder surrounded by a weave of jute yarn and wire, lacquered for protection against rain, easily lit thanks to a shard of flint wired to the end of the wick and surrounded by a blob of powder; inside the sheet metal screw top that covers the fuse can be found a piece of sandpaper. In other words, each model came with a weatherproof match attached to the wick. The n 1 came to be known as the tonelete, or barrel, due to its shape. Its body was segmented on the outside in the style of typical first generation fragmentation grenades; we now know that segmentation of this type on the interior of the body is more conducive to fragmentation, hence the smooth exteriors of modern frags.

By 1921 an order of 50,000 n 1 tonelete grenades was shipped to Africa by the Spanish Army. The Tonelete did not use a high explosive compound at the time, relying upon a 45 gram mixture of three parts “gunpowder” and one part rosin, the gunpowder verified by sources as black powder. The original model tonelete used a separate cast, threaded plug to hold the fuse, possibly for shipping safety or ease of manufacture, but in later years it changed to a single body with only a threaded plug for the base, through which the powder charge was filled.

While more complex mechanical fuses may have been ultimately desirable, at the outbreak of the Civil War the belligerent Republican forces needed grenades immediately, so it was quite straightforward for local industry to reverse engineer the Tonelete. The “Piño,” a variety developed at the Madrid Artillery Park, it was manufactured to a very high standard with a handful of design simplifications, such as an un-threaded cap area over which a rubber plug was pressed to protect the fuse from moisture and damage.

Other tonelete-style grenades, whether copies or variations on the basic theme, were developed all around Spain; some larger, some smaller, some with wooden handles, others using TNT or other explosives with a mercury fulminate detonator at the end of the fuse. Cast iron manufacturing is quite simple; watch the video “Making Mills Bombs” to see original footage from New Zealand demonstrating the concept.

German Grenades Were Simple and Inexpensive

Germany’s innovative population and industrial might have long allowed their nation to leapfrog others in technical advancements which simply do not occur to other peoples. The German BZ-24 friction igniter fuse represented below may appear complex, but in fact is an elegant manifestation of a simple concept which the Spanish did not copy until after the close of the war. The United States saw this type of fuse adopted by our military for demolitions and variations on the theme are still used in commercial blasting. Marine parachute flares, as commonly found in private boats and only costing a few dollars, use precisely the same type of ignition mechanism – minus the delay pellet and mercury fulminate detonator.

Expedient Hand Grenades by George Dmitrieff, now out of print, is a fine book available for free in PDF format from a variety of online archive sites which details the manner in which one may fabricate a friction-igniter pull type fuse in a small shop if LAWFULLY LEGAL to do so – don’t be a silly goose! Perhaps someday your local magistrate will have occasion to pin a shiny, shiny badge upon your shirt and this type of information may come in handy.